Step 9 of 9

Risk of endocarditis

Patients suffering from some congenital heart diseases are at risk of endocarditis. However, their prognosis is generally better than that for other heart diseases (mortality < 10%) [8]. They must be given antibiotic prophylaxis in any surgery where bacterial contamination is certain. Having been widely prescribed for many years, antibiotic prophylaxis is currently limited to high-risk situations, since there is little evidence of its efficacy [11]. The risk is highest among patients who are carriers of prosthetic equipment (patches, valves, conduits), and those with lesions involving high-velocity jets: VSD, tetralogy of Fallot, AV canal defects, valve insufficiency [4]. Indeed high-velocity jets are a cause of endothelial lesions resulting in the deposit of platelets and fibrin. In cases of bacteraemia, organisms can easily colonise these lesions and develop a focus for endocarditis [7]. The risk is lower if the lesions include low-velocity flows (ASD, PFO) and is low for isolated VSDs or in case of surgical correction with autologous pericardium [9]. Once implanted equipment has been completely endothelialised (i.e. on average after 6 months), bacterial risk is minimal.

Prophylaxis against endocarditis is currently recommended in the following circumstances [1,3,5,6,7,10].

Prophylaxis against endocarditis is currently recommended in the following circumstances [1,3,5,6,7,10].

- Valve prosthesis;

- Uncorrected cyanotic heart disease;

- Residual lesion post-operation, palliative shunt;

- Prosthetic equipment implanted surgically or percutaneously less than 6 months previously – this indication continues for life in the event of residual lesions;

- History of endocarditis;

- Immunosuppression (transplantation).

The best prophylaxis is impeccable hygiene, in particular oral, dental and skin hygiene. Tattoos and piercings, especially of the tongue and mucous membranes, should be avoided [6].

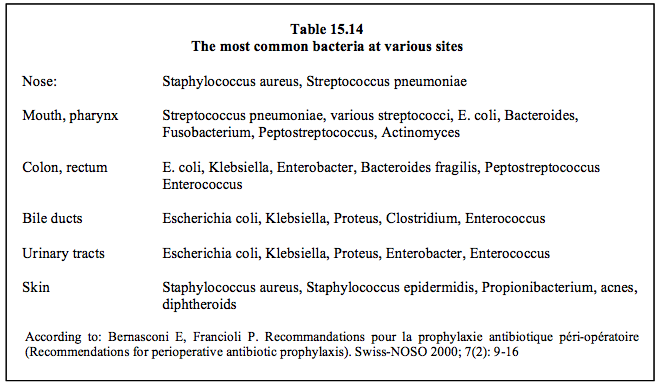

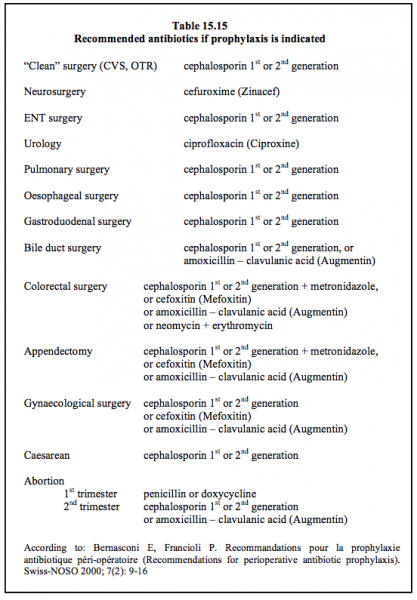

These recommendations only apply to septic surgery and dental procedures involving opening the gums or periapical region. Antibiotic prophylaxis is not routinely recommended for digestive, respiratory, neurological, genitourinary, dermatological or orthopaedic procedures, unless such action is necessary due to the patient's infectious state or local contamination [1]. The type of antibiotic prescribed depends on the type of bacterial contamination (Table 15.14 and Table 15.15) [2]. Antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended for all operations in cardiac surgery.

© BETTEX D, CHASSOT PG, January 2008, last update May 2018

References

These recommendations only apply to septic surgery and dental procedures involving opening the gums or periapical region. Antibiotic prophylaxis is not routinely recommended for digestive, respiratory, neurological, genitourinary, dermatological or orthopaedic procedures, unless such action is necessary due to the patient's infectious state or local contamination [1]. The type of antibiotic prescribed depends on the type of bacterial contamination (Table 15.14 and Table 15.15) [2]. Antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended for all operations in cardiac surgery.

| Indications for prophylaxis against endocarditis in congenital heart patients |

| Antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended in the following situations: - Valve prosthesis - Unoperated cyanotic heart diseases, persistent cyanosis - Prosthetic equipment implanted for < 6 months or with a residual lesion - History of endocarditis |

© BETTEX D, CHASSOT PG, January 2008, last update May 2018

References

- BAUMGARTNER H, BONHOEFFER P, DE GROOT NMS, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of grown-up congenital heart disease (new version 2010). Eur Heart J 2010; 31:2915-57

- BERNASCONI E, FRANCIOLI P. Recommandations pour la prophylaxie antibiotique péri-opératoire. Swiss-NOSO 2000; 7(2): 9-16

- BOUCHARDY J, PRÊTRE R. Cardiopathies congénitales: prise en charge du patient adulte. Forum Med Suisse 2014; 14:311-3

- DAJANI AS, BISNO AL, CHUNG KJ, et al. Prevention of bacterial endocarditis. Recommandations by the American Heart Association.. JAMA 1990; 264:2919-22

- HABIB G, HOEN B, TORNOS P, et al. Guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of infective endocarditis (new version 2009). Eur Heart J 2009; 30:2369-413

- LANCELOTTI P, ANTUNES MJ, BONGIORNI MG, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis. Eur Heart J 2015; 36:3075-123

- NISHIMURA RA, CARABELLO BA, FAXON DP, et al. 2008 Guideline update on valvular heart disease: focused update on infective endocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 52:676-85

- NISHIMURA RA, OTTO CM, RIGOLIN VH, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 70:252-89

- SILVERSIDES CK, DORE A, POIRIER N, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society 2009 Consensus Conference on the management of adults with congenital heart disease: Shunt lesions. Can J Cardiol 2010; 26:e70-e79

- WARNES CA, WILLIAMS RG, BASHORE TM, et al. ACC/AHA 2008 Guidelines for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: executive summary. Circulation 2008; 118:2395-451

- WILSON W, TAUBERT KA, GEWITZ M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis. Guidelines from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2007; 116:1736-54

15. Anesthesia for adult congenital heart disease patients

- 15.1 Introduction

- 15.2 Nomenclature and pathophysiology

- 15.3 Approach by pathology

- 15.3.1 Classification

- 15.3.2 Diagnostic methods

- 15.3.3 Anomalous venous returns

- 15.3.4 Atrial septal defects (ASDs)

- 15.3.5 Atrioventricular canal (AVC) defects

- 15.3.6 Ebstein anomaly

- 15.3.7 Ventricular septal defects (VSDs)

- 15.3.8 Ventricular hypoplasia

- 15.3.9 Tetralogy of Fallot

- 15.3.10 Mixed shunt

- 15.3.11 Pulmonary stenosis

- 15.3.12 Anomalies of the LV ejection pathway

- 15.3.13 Transposition of the great arteries (TGA

- 15.3.15 Coarctation of the aorta

- 15.3.14 Congenitally corrected TGA

- 15.3.16 Arterial abnormalities

- 15.4 General considerations for anesthesia

- 15.5 Conclusions