Step 11 of 16

Pulmonary stenosis

While pulmonary stenosis is present in approximately 10% of congenital heart disease cases, it may also exist in isolation and manifest in adulthood as right ventricular hypertrophy followed by RV failure. The RV is often ischaemic as the O2 requirement is raised while O2 delivery is compromised by intraventricular hypertension during systole. An increase in afterload occurring from birth, as is the case in pulmonary stenosis, causes concentric-type hypertrophy rather than RV dilation. Right heart function remains adequate as long as intraventricular pressure is < 50% of left heart pressure. Patients become symptomatic if RV pressure exceeds half of systemic pressure or if volume overload is added (TI, shunt) [8].

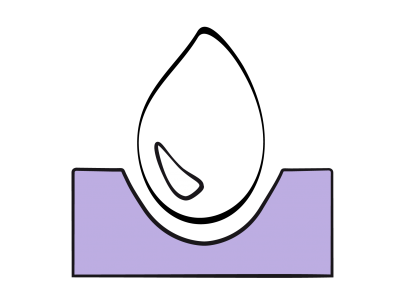

The valve is dome-shaped with a narrowed central opening. Surgery is indicated if the maximum gradient is ≥ 50 mmHg and the mean gradient ≥ 30 mmHg [1,2,6,8]. Percutaneous valve repair by balloon dilation is the preferred treatment [7]. It is associated with severe pulmonary insufficiency in 25% of adult cases [3]. Although more invasive, surgical valvulotomy leads to excellent outcomes and 95% survival at 25 years. Using transcatheter-implantable prostheses, a less invasive route for pulmonary valve replacement, is possible. However, this technique should only be considered if there is a sufficiently firm support into which to anchor the prosthesis, e.g. a previous valved conduit [2,5].

Double-chambered right ventricle

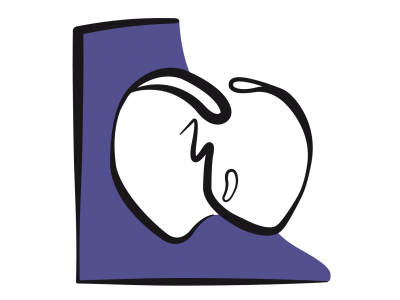

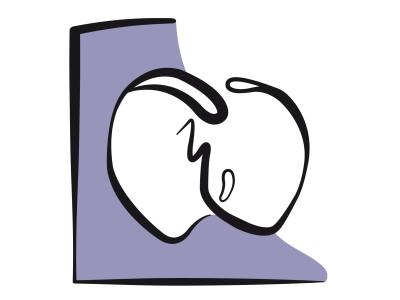

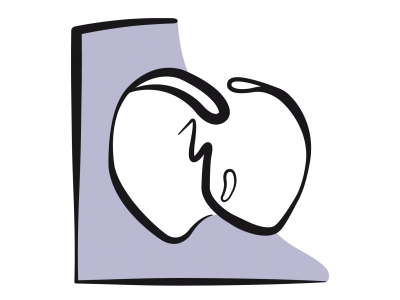

The division of the RV into two separate chambers by a wide muscular trabecula located at the base of the infundibulum is an unusual type of RVOT obstruction. It is frequently misinterpreted as pulmonary hypertension, since pressure is high in the proximal chamber, and because it causes high velocity in the tricuspid insufficiency jet. This pathology is often associated with a VSD [2]. Surgical resection is indicated if the intraventricular pressure gradient is > 30 mmHg [4].

Anaesthesia

Four key challenges are faced in the anaesthetic management of pulmonary stenosis:

The valve is dome-shaped with a narrowed central opening. Surgery is indicated if the maximum gradient is ≥ 50 mmHg and the mean gradient ≥ 30 mmHg [1,2,6,8]. Percutaneous valve repair by balloon dilation is the preferred treatment [7]. It is associated with severe pulmonary insufficiency in 25% of adult cases [3]. Although more invasive, surgical valvulotomy leads to excellent outcomes and 95% survival at 25 years. Using transcatheter-implantable prostheses, a less invasive route for pulmonary valve replacement, is possible. However, this technique should only be considered if there is a sufficiently firm support into which to anchor the prosthesis, e.g. a previous valved conduit [2,5].

Double-chambered right ventricle

The division of the RV into two separate chambers by a wide muscular trabecula located at the base of the infundibulum is an unusual type of RVOT obstruction. It is frequently misinterpreted as pulmonary hypertension, since pressure is high in the proximal chamber, and because it causes high velocity in the tricuspid insufficiency jet. This pathology is often associated with a VSD [2]. Surgical resection is indicated if the intraventricular pressure gradient is > 30 mmHg [4].

Anaesthesia

Four key challenges are faced in the anaesthetic management of pulmonary stenosis:

- Risk of RV ischaemia – maintain systemic pressure with arterial vasconstrictors to ensure right coronary perfusion;

- Risk of hypovolaemia – blood flow from the hypertrophied RV is highly dependent on its preload. In addition to the stenosis effect, hypovolaemia therefore prompts a significant drop in pulmonary blood flow and arterial desaturation;

- Management of right-sided dysfunction;

- Management of arrhythmias (mainly ventricular).

A sudden increase in pulmonary blood flow once the obstacle is removed may result in a pulmonary reperfusion lesion in a quarter of cases. This manifests as pulmonary oedema, a PaO2/Fi O2 ratio < 250 and infiltrates on X-ray [9].

© BETTEX D, CHASSOT PG, January 2008, last update February 2020

References

| Pulmonary stenosis |

| Isolated pulmonary stenosis causes RV hypertrophy and secondarily results in right-sided decompensation if P RV is more than twice as high as P LV. Surgical indication: mean gradient > 30 mmHg. Anaesthesia: - Maintain systemic AP (vasoconstrictor) - Maintain preload - Inotropic support of the RV - Risk of ventricular arrhythmia |

© BETTEX D, CHASSOT PG, January 2008, last update February 2020

References

- BAUMGARTNER H, BONHOEFFER P, DE GROOT NMS, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of grown-up congenital heart disease (new version 2010). Eur Heart J 2010; 31:2915-57

- BHATT AB, FOSTER E, KUEHL K, et al. Congenital hesart disease in older adult. A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015; 131:1884-931

- FAWZY ME, HASSAN W, FADEL BM, et al. Long-term results (up to 17 years) of pulmonary balloon valvuloplasty in adults and its effects on concomitant severe infundibular stenosis and tricuspid regurgitation. Am Heart J 2007; 153:433-8

- McELHINNEY DB, CHATTERJEE KM; REDDY VM. Double-chambered right ventricle presenting in adulthood. Ann Thorac Surg 2000; 70:124-7

- NISHIMURA RA, OTTO C, BONOW RO, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014; 129:e521-e643

- SILVERSIDES CK, KIESS M, BEAUCHESNE L, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society 2009 Consensus Conference on the management of adults with congenital heart disease: Outflow tract obstruction, coarctation of the aorta, tetralogy of Fallot, Ebstein anomaly and Marfan’s syndrome. Can J Cardiol 2010; 26:e80-e97

- STOUT KK, DANIELS CJ, VALENTE AM, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC Guideline for the management of adults with congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019; 73:e81-192

- WARNES CA, WILLIAMS RG, BASHORE TM, et al. ACC/AHA 2008 Guidelines for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: executive summary. Circulation 2008; 118:2395-451

- YACOUBY S, MEADOR M, MOSSAD E. Lung reperfusion injury in patients after balloon angioplasty for pulmonary artery stenosis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2014; 28:502-5

15. Anesthesia for adult congenital heart disease patients

- 15.1 Introduction

- 15.2 Nomenclature and pathophysiology

- 15.3 Approach by pathology

- 15.3.1 Classification

- 15.3.2 Diagnostic methods

- 15.3.3 Anomalous venous returns

- 15.3.4 Atrial septal defects (ASDs)

- 15.3.5 Atrioventricular canal (AVC) defects

- 15.3.6 Ebstein anomaly

- 15.3.7 Ventricular septal defects (VSDs)

- 15.3.8 Ventricular hypoplasia

- 15.3.9 Tetralogy of Fallot

- 15.3.10 Mixed shunt

- 15.3.11 Pulmonary stenosis

- 15.3.12 Anomalies of the LV ejection pathway

- 15.3.13 Transposition of the great arteries (TGA

- 15.3.15 Coarctation of the aorta

- 15.3.14 Congenitally corrected TGA

- 15.3.16 Arterial abnormalities

- 15.4 General considerations for anesthesia

- 15.5 Conclusions