Step 14 of 16

Coarctation of the aorta

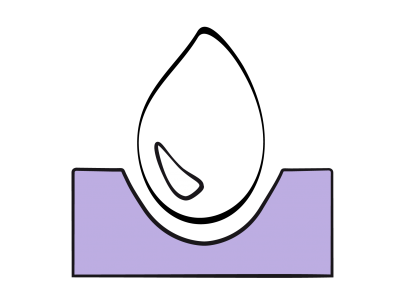

Coarctation of the aorta is an hour-glass shaped narrowing of varying length or a membrane-type stenosis. It is located just after the left subclavian artery root at the site of the ligamentum arteriosum (Video and Figure 15.59).

Video: Long-axis view (90°) of the descending aorta with a coarctation; colour flow shows a prestenotic acceleration zone (on the right of the screen) and a turbulent high-velocity flow distal to the stenosis (towards the left handside of the screen).

Figure 15.59: Coarctation of the aorta. A: membrane at the site of the isthmus. B: colour flow Doppler with a concentric acceleration zone (proximal isovelocity surface area: PISA) upstream and turbulence downstream of the membrane (arrow).

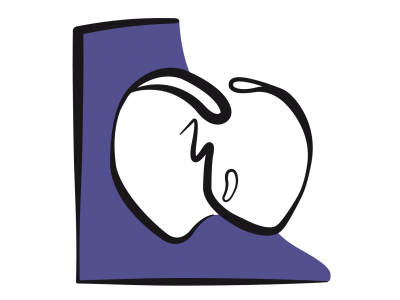

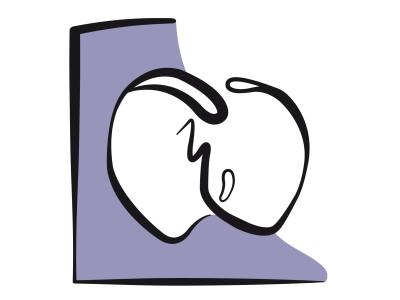

It occurs in 0.3% of births [3] and is often associated with a bicuspid aortic valve (over 50% of cases) and a patent ductus arteriosus (20% of cases). It is characterised by hypertension in the upper limbs and hypotension in the lower limbs. The pressure gradient between measurements in the upper limb and lower limb is over 20 mmHg. Differences in pulse may only emerge on exercise. TEE reveals that thoracic aorta pulsatility is high above the lesion, but very low below it (Videos).

Video: Short-axis view of the descending aorta above the coarctation; the aortic pulsatility is exagerated.

Video: Short-axis view of the descending aorta downstream the coarctation; the aortic pulsatility is decreased.

The coarctation imposes very high afterload on the LV, which hypertrophies concentrically as in aortic stenosis. Systolic function is generally preserved, but diastolic function is severely impaired. An extensive collateral system of periscapular, internal mammary, cervical and intercostal arteries ensures perfusion below the lesion. Dilated intercostal arteries create notches, which can be seen on the lower border of the ribs on a chest X-ray. Auscultation reveals a 3/6 systolic murmur in the posterior left mid-thoracic region. These patients generally die in early adulthood (mean survival age: 34 years) of left-sided congestive failure, endocarditis, rupture of thoracic aorta, or brain haemorrhage [11]. Surgery is indicated if the gradient is ≥ 20 mmHg or if major collateralisation is present even if the gradient is lower [1,9,10]. Even if corrected during childhood, recoarctation of the aorta may recur in young adults [2]. Moreover, 20-30% of patients who have undergone surgery present with persistent arterial hypertension even though the obstruction has been removed [6].

Percutaneous dilation with placement of a stent is the preferred treatment for young adults with suitable anatomy [9]. It is less invasive and avoids the risk of aortic clamping and medullary ischaemia [1,8,9]. The main risk of surgery is aortic clamping. Risk is dependent on the density of intercostal collaterals “bypassing” the stenosis (see Chapter 18 Descending aorta, Anaesthesia). It increases if the pressure gradient between the right arm and the lower limbs is low, since in this case, there is little development of collateralisation. The stenosis is usually short and anastomosis can be performed end-to-end. A patch made from the left subclavian artery prevents any residual stenosis. The aorta is clamped for no more than 30 minutes. If the lesion is long, resection and a tubular bypass graft are necessary.

During clamping, upstream pressure is measured in the right arm (radial catheter) and downstream pressure is measured in a femoral line (femoral catheter). Distal pressure below the clamp must be kept at ≥ 60 mmHg with arterial vasoconstrictors (norepinephrin, phenylephrine) to facilitate pressure-dependent flow through the collaterals and to limit the risk of medullary ischaemia. Since surgery is performed by left-sided thoracotomy, a double lumen tube is recommended in order to exclude the left lung. Postoperatively, a drop in diastolic pressure is a good indicator that the pressure gradient has disappeared. The incidence of postoperative paraplegia secondary to medullary ischaemia is 0.1-0.4% of patients [4].

Arterial hypertension is common after correction [7]. This postoperative hypertension peaks at 12-24 hours, probably due to discharges of baroreceptors set for supra-lesional hypertension, and a second phase after 2-3 days linked to excessive levels of renin and angiotensin. This and LV hypertrophy persists in 20-50% of patients [5]. In the days following surgery, mesenteric arteritis is common. It is caused by sympathetic hyperactivity and presents as abdominal pain.

© BETTEX D, CHASSOT PG, January 2008, last update February 2020

References

Video: Long-axis view (90°) of the descending aorta with a coarctation; colour flow shows a prestenotic acceleration zone (on the right of the screen) and a turbulent high-velocity flow distal to the stenosis (towards the left handside of the screen).

Figure 15.59: Coarctation of the aorta. A: membrane at the site of the isthmus. B: colour flow Doppler with a concentric acceleration zone (proximal isovelocity surface area: PISA) upstream and turbulence downstream of the membrane (arrow).

It occurs in 0.3% of births [3] and is often associated with a bicuspid aortic valve (over 50% of cases) and a patent ductus arteriosus (20% of cases). It is characterised by hypertension in the upper limbs and hypotension in the lower limbs. The pressure gradient between measurements in the upper limb and lower limb is over 20 mmHg. Differences in pulse may only emerge on exercise. TEE reveals that thoracic aorta pulsatility is high above the lesion, but very low below it (Videos).

Video: Short-axis view of the descending aorta above the coarctation; the aortic pulsatility is exagerated.

Video: Short-axis view of the descending aorta downstream the coarctation; the aortic pulsatility is decreased.

The coarctation imposes very high afterload on the LV, which hypertrophies concentrically as in aortic stenosis. Systolic function is generally preserved, but diastolic function is severely impaired. An extensive collateral system of periscapular, internal mammary, cervical and intercostal arteries ensures perfusion below the lesion. Dilated intercostal arteries create notches, which can be seen on the lower border of the ribs on a chest X-ray. Auscultation reveals a 3/6 systolic murmur in the posterior left mid-thoracic region. These patients generally die in early adulthood (mean survival age: 34 years) of left-sided congestive failure, endocarditis, rupture of thoracic aorta, or brain haemorrhage [11]. Surgery is indicated if the gradient is ≥ 20 mmHg or if major collateralisation is present even if the gradient is lower [1,9,10]. Even if corrected during childhood, recoarctation of the aorta may recur in young adults [2]. Moreover, 20-30% of patients who have undergone surgery present with persistent arterial hypertension even though the obstruction has been removed [6].

Percutaneous dilation with placement of a stent is the preferred treatment for young adults with suitable anatomy [9]. It is less invasive and avoids the risk of aortic clamping and medullary ischaemia [1,8,9]. The main risk of surgery is aortic clamping. Risk is dependent on the density of intercostal collaterals “bypassing” the stenosis (see Chapter 18 Descending aorta, Anaesthesia). It increases if the pressure gradient between the right arm and the lower limbs is low, since in this case, there is little development of collateralisation. The stenosis is usually short and anastomosis can be performed end-to-end. A patch made from the left subclavian artery prevents any residual stenosis. The aorta is clamped for no more than 30 minutes. If the lesion is long, resection and a tubular bypass graft are necessary.

During clamping, upstream pressure is measured in the right arm (radial catheter) and downstream pressure is measured in a femoral line (femoral catheter). Distal pressure below the clamp must be kept at ≥ 60 mmHg with arterial vasoconstrictors (norepinephrin, phenylephrine) to facilitate pressure-dependent flow through the collaterals and to limit the risk of medullary ischaemia. Since surgery is performed by left-sided thoracotomy, a double lumen tube is recommended in order to exclude the left lung. Postoperatively, a drop in diastolic pressure is a good indicator that the pressure gradient has disappeared. The incidence of postoperative paraplegia secondary to medullary ischaemia is 0.1-0.4% of patients [4].

Arterial hypertension is common after correction [7]. This postoperative hypertension peaks at 12-24 hours, probably due to discharges of baroreceptors set for supra-lesional hypertension, and a second phase after 2-3 days linked to excessive levels of renin and angiotensin. This and LV hypertrophy persists in 20-50% of patients [5]. In the days following surgery, mesenteric arteritis is common. It is caused by sympathetic hyperactivity and presents as abdominal pain.

| Coarctation of the aorta |

| Characteristics: - Arterial hypertension in the upper limbs, arterial hypotension in the lower limbs (ΔP > 20 mmHg) - Concentric LVH - Thoracic collateral system Anaesthesia recommendations: - Double-lumen tube (left thoracotomy) - Pre-ductal arterial pressure measured by right radial catheter and post-ductal arterial pressure by femoral catheter - During clamping: maintain post-ductal pressure > 60 mmHg (alpha vasoconstrictor) - Post-clamping: hypertensive crisis, mesenteric arteritis, risk of paraplegia |

© BETTEX D, CHASSOT PG, January 2008, last update February 2020

References

- BAUMGARTNER H, BONHOEFFER P, DE GROOT NMS, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of grown-up congenital heart disease (new version 2010). Eur Heart J 2010; 31:2915-57

- BROUWER RMHJ, ERASMUS ME, EBELS T EIJGELAAR A. Influence of age on survival , late hypertension, and recoarctation in elective aortic coarctation repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1994; 108:525-31

- KAEMMERER H. Aortic coarctation and interrupted aortic arch. In GATZOULIS MA, et al, Eds. Diagnosis and management of adult congenital heart disase. Edinburgh: Churchill-Livingstone 2003, 253-64

- KEEN G. Spinal cord damage and operations for coarctation of the aorta: aetiology, practice and propects. Thorax 1987; 42:11-8

- MALAN JE, BENATAR A, LEVIN SE. Long-term follow-up of coarctation of the aorta repaired by patch angioplasty. Int J Cardiol 1991; 30:23-9

- McGOWAN FX. Perioperative issues in patients with congenital heart disease. IARS lectures. Anesth Analg 2005; 100:S53-S61

- PRESBITERO P, DEMARIE D, VILLANI M, et al. Long-term results (20-30 years) of surgical repair of aortic coarctation. Br Heart J 1987; 57:462-7

- SILVERSIDES CK, KIESS M, BEAUCHESNE L, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society 2009 Consensus Conference on the management of adults with congenital heart disease: Outflow tract obstruction, coarctation of the aorta, tetralogy of Fallot, Ebstein anomaly and Marfan’s syndrome. Can J Cardiol 2010; 26:e80-e97

- STOUT KK, DANIELS CJ, VALENTE AM, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC Guideline for the management of adults with congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019; 73:e81-192

- WARNES CA, WILLIAMS RG, BASHORE TM, et al. ACC/AHA 2008 Guidelines for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: executive summary. Circulation 2008; 118:2395-451

- WHITROCK K. Anesthesia for surgery to repair aortic coarctation. In: SIMPSON JI, ed. Anesthesia for aortic surgery. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann 1997, 199-227

15. Anesthesia for adult congenital heart disease patients

- 15.1 Introduction

- 15.2 Nomenclature and pathophysiology

- 15.3 Approach by pathology

- 15.3.1 Classification

- 15.3.2 Diagnostic methods

- 15.3.3 Anomalous venous returns

- 15.3.4 Atrial septal defects (ASDs)

- 15.3.5 Atrioventricular canal (AVC) defects

- 15.3.6 Ebstein anomaly

- 15.3.7 Ventricular septal defects (VSDs)

- 15.3.8 Ventricular hypoplasia

- 15.3.9 Tetralogy of Fallot

- 15.3.10 Mixed shunt

- 15.3.11 Pulmonary stenosis

- 15.3.12 Anomalies of the LV ejection pathway

- 15.3.13 Transposition of the great arteries (TGA

- 15.3.15 Coarctation of the aorta

- 15.3.14 Congenitally corrected TGA

- 15.3.16 Arterial abnormalities

- 15.4 General considerations for anesthesia

- 15.5 Conclusions